Taking Stock: Numbers don’t lie (except when they do)

The anonymous reviewer of books by Nicholson Baker (in 2001) and Richard Cox (in 2002) excerpted below will be revealed later. (This is a book review contest set up by Scott Alexander, who produces the always-interesting newsletter 'Astral Codex Ten' [successor to the always-interesting newsletter 'Slate Star Codex'], from which these anonymous book review excerpts are taken.)

'If you enter a major research library in the US today and request to see a century-old issue of a major American newspaper, such as Chicago Tribune, The Wall Street Journal, or major-but-defunct newspapers such as the New York “World,” odds are that you will be directed to a computer or a microfilm reader. There, you’ll get to see black-and-white images of the desired issue, with individual numbers of the newspaper often missing and much of the text, let alone pictures, barely decipherable.

The libraries in question mostly once had bound issues of these newspapers, but between the 1950s and the 1990s, one after another, they ditched the originals in favor of expensive microfilmed copies of inferior quality.

'They continued doing this even while the originals became perilously rare; the newspapers themselves were mostly trashed, or occasionally sold to dealers who cut them up and dispersed them.

As a consequence, many of these publications are now rarer than the Gutenberg Bible, and some 19th and 20th century newspapers have ceased to exist in a physical copy anywhere in the world.

'When Double Fold by Nicholson Baker came out in 2001, it was described as The Jungle of the American library system. After 20 years, the book remains universally known, sometimes admired but often despised, among librarians. The reason for their belligerence is that Baker publicly revealed a decades-long policy of destruction of primary materials from the 19th and 20th centuries, based on a pseudoscientific notion that books on wood-pulp paper are quickly turning to dust, coupled with a misguided futuristic desire to do away with outdated paper-based media. . . .'

As a consequence, perfectly well preserved books with centuries of life still ahead of them were hastily replaced with an inferior medium which has, at the moment that I am writing this review, already mostly gone the way of the dodo.

astralcodexten.substack.com

A revolution is sweeping the science of ancient diseases—Sarah Zhang

The study of DNA from millennia-old bacteria and viruses is revealing new secrets about the plague and other epidemics.

Sarah Zhang here interviews Johannes Krause, director of the archaeogenetics department at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

'. . . [Y]ou can . . . find DNA from ancient pathogens in old bones. The “junk” might actually contain clues about long-ago pandemics. Over the past decade, scientists have used ancient DNA to study diseases including the plague, syphilis, hepatitis B, and a mysterious “cocoliztli” epidemic—all using techniques honed through decoding the Neanderthal genome. A boom in ancient pathogen DNA is uncovering hints of forgotten and even extinct diseases. . . .

Krause: 'Blood is what we’re actually looking for, because most of the pathogens we’re looking at—hepatitis B or Yersinia pestis—they are actually blood-borne. But how do you get a blood sample from 600 years ago? The tooth is the best place for blood samples because teeth are vascularized, so you have blood flow inside the teeth. And the teeth are protected by the enamel. They’re like a little time capsule. . . .

We are creating niches for pathogens.

'We ourselves only became an interesting host in the last 10,000 years, when we started agriculture and having large populations and a sedentary lifestyle where we live with a lot of people in the same place and dump our excrement behind our houses. Basically we are surrounded by garbage, and that attracts a lot of rodents and potential parasites of those rodents.

'It’s only from that point, where the population size is big enough, that infectious disease can spread and can be passed on between one population and another—only then it becomes a human pathogen. We’ve become even a better and more interesting host, like we've seen with coronavirus, right? It took three weeks, and it was in almost every country in the world.'

. . . [H]umans have become like bats because we now have dense populations. Bats live in these really dense populations, like millions sometimes in one cave.

But unlike bats, we have only had 5,000 years to adapt, and bats have done that for the last 40 million years.

But we have our big brains and really powerful medicine.

theatlantic.com | @TheAtlantic | @sarahzhang

What data can—and can't—do—Hannah Fry (heard through Albert Chu's superb Substack newsletter Links)

Seduced by their seeming precision and objectivity, we can feel betrayed when the numbers fail to capture the unruliness of reality.

'. . . Goodhart’s law is really just hinting at a much more basic limitation of a data-driven view of the world. As Tim Harford writes, data “may be a pretty decent proxy for something that really matters,” but there’s a critical gap between even the best proxies and the real thing—between what we’re able to measure and what we actually care about. . . .

Even the tiniest fluctuations, invisible to science, can magnify over time to yield a world of difference. Nature is built on unavoidable randomness, limiting what a data-driven view of reality can offer.

'. . . [I]f more data isn’t always the answer, maybe we need instead to reassess our relationship with predictions—to accept that there are inevitable limits on what numbers can offer, and to stop expecting mathematical models on their own to carry us through times of uncertainty.

'Numbers are a poor substitute for the richness and color of the real world. It might seem odd that a professional mathematician (like me) or economist (like Harford) would work to convince you of this fact. But to recognize the limitations of a data-driven view of reality is not to downplay its might. It’s possible for two things to be true: for numbers to come up short before the nuances of reality, while also being the most powerful instrument we have when it comes to understanding that reality.

'The events of the pandemic offer a trenchant illustration. The statistics can’t capture the true toll of the virus. They can’t tell us what it’s like to work in an intensive-care unit, or how it feels to lose a loved one to the disease. They can’t even tell us the total number of lives that have been lost (as opposed to the number of deaths that fit into a neat category, such as those occurring within twenty-eight days of a positive test). They can’t tell us with certainty when normality will return. But they are, nonetheless, the only means we have to understand just how deadly the virus is, figure out what works, and explore, however tentatively, the possible futures that lie ahead.'

Numbers can contain within them an entire story of human existence. In Kenya, forty-three children out of every thousand die before their fifth birthday. In Malaysia, only nine do. . . .

newyorker.com | @NewYorker

And a few numbers that should give us Homo sapiens pause—Jason Daley (found again via Albert Chu's excellently curated Links newsletter)

Humans make up just 1/10,000 of Earth’s biomass.

'The human population on Earth is about 7.6 billion people (and counting). But according to a new global census of biomass, humans are barely a rounding error compared to the rest of life on Earth. As Seth Borenstein at The Associated Press reports, the biomass of humanity—measured by the dry-weight of carbon that makes up our bodies—is equivalent to just one ten-thousandth of all biomass on our planet.

'Anyone who has walked through a jungle or wandered a grassland may already have guessed that humans are a pretty small part of Earth’s organic matter. The carbonaceous winners are plants, which make up about 80 percent of all bio

mass on Earth. Bacteria comes in second at 13 percent and fungus is third at just 2 percent.

'Of the 550 gigatons of biomass carbon on Earth, animals make up about 2 gigatons, with insects comprising half of that and fish taking up another 0.7 gigatons. Everything else, including mammals, birds, nematodes and mollusks are roughly 0.3 gigatons, with humans weighing in at 0.06 gigatons. The research appears in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. . . .'

smithsonianmag.com | @SmithsonianMag

Global vaccine crisis sends ominous signal for fighting climate change—Somini Sengupta

The gap between rich and poor countries on vaccinations highlights the failure of richer nations to see it in their self-interest to urgently help poorer ones fight a shared crisis.

The stark gap in vaccination rates between the world’s rich and poor countries is emerging as a test for how the world responds to that other global challenge: averting the worst effects of climate change.

'Of the more than 1.1 billion vaccinations administered globally, the vast majority have gone into the arms of people who live in the wealthiest countries. The United States, where nearly half the population has received at least one dose, sits on millions of surplus doses, while India, with a 9 percent vaccination rate, shatters records in new daily infections. In New York City, you hear cries of relief at the chance to breathe free and unmasked; in New Delhi, cries for oxygen.

'The vaccine gap presents an object lesson for climate action because it signals the failure of richer nations to see it in their self-interest to urgently help poorer ones fight a global crisis. That has direct parallels to global warming. Poor countries consistently assert that they need more financial and technological help from wealthier ones if the world as a whole is going to avoid the worst consequences of climate change. So far, the richest countries—which are also the biggest emitters of greenhouse gases—haven’t come up with the money. . . .

'The next few weeks will be critical, as world leaders gather for meetings of the seven richest countries, the Group of 7, in June and then of the finance ministers of the world’s 20 biggest economies, the Group of 20, in July. Those meetings will then be followed by the U.N.-led climate negotiations in Glasgow in November. . . .'

nytimes.com | @nytimes | @SominiSengupta

India’s Covid crisis could happen anywhere—Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo

It will be a while before it’s fully understood why India has been so swiftly and so disastrously engulfed by the coronavirus. But there is one thing for sure: India’s problem is now the world’s problem.

'India shut down too abruptly when the virus arrived, and then was too quick to reopen. In March 2020, the country was locked down at four hours’ notice though it did not yet have many cases. Millions of people, many of them migrant workers, were left stranded without food and shelter. Facing economic disaster, the government reopened the country before the pandemic really took hold.

'What is happening in India now is quite similar to what the United States experienced in its coronavirus surges. The Indian states where deaths started to mount again in March and April simply closed their eyes and hoped it would go away. After all, India’s first virus wave receded, for reasons that remain unclear. . . .'

nytimes.com | @nytimes

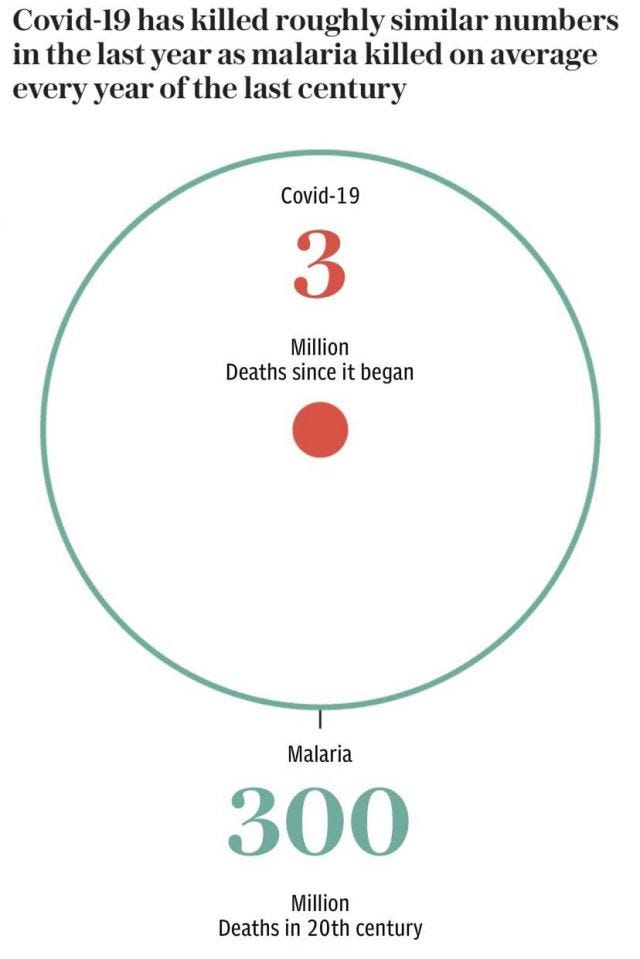

Keeping things in perspective

From ILRI's David Aronson via the Telegraph.

News bites

'[G]iven that all countries reside in the world, and the world isn’t immunized, herd immunity may only last so long. The lesson of 2020, learned well in Israel, is that the world is connected, and in a sense the herd isn’t one country, the herd is the world.'—Ronen Ben-Ami, director of infectious diseases at Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, via The Times of Israel

Term of the week

Lachryphagy: When one animal drinks the tears of another.

These butterflies aren’t just giving this caiman pretty decoration.

The ones on its eyes are sipping on the reptile’s tears.

(Photo by EACHAT/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS)

Arresting headlines

Senate confirms Samantha Power to be U.S.A.I.D. Administrator—New York Times

EU calls for rethink of GMO rules for gene-edited crops, opening the door to a possible loosening of restrictions for plants resulting from gene-editing technology—Reuters

We found methane-eating bacteria living in a common Australian tree. It could be a game changer for curbing greenhouse gases—The Conversation

U.S. will back proposal to waive patent rights and boost Covid-19 vaccine production—STAT News

Canada authorizes coronavirus vaccine for children ages 12 to 15—Washington Post

Subscribe to the weekly Taking Stock newsletter

and see previous issues

Numbers don't lie (except when they do)