Foreign aid—Hannah Ritchie

‘Most countries spend less than 1% of their national income on foreign aid; even small increases could make a big difference

‘Foreign aid has played a crucial role in improving the lives of millions around the world, from supplying food during famines to fighting diseases such as polio, HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis.

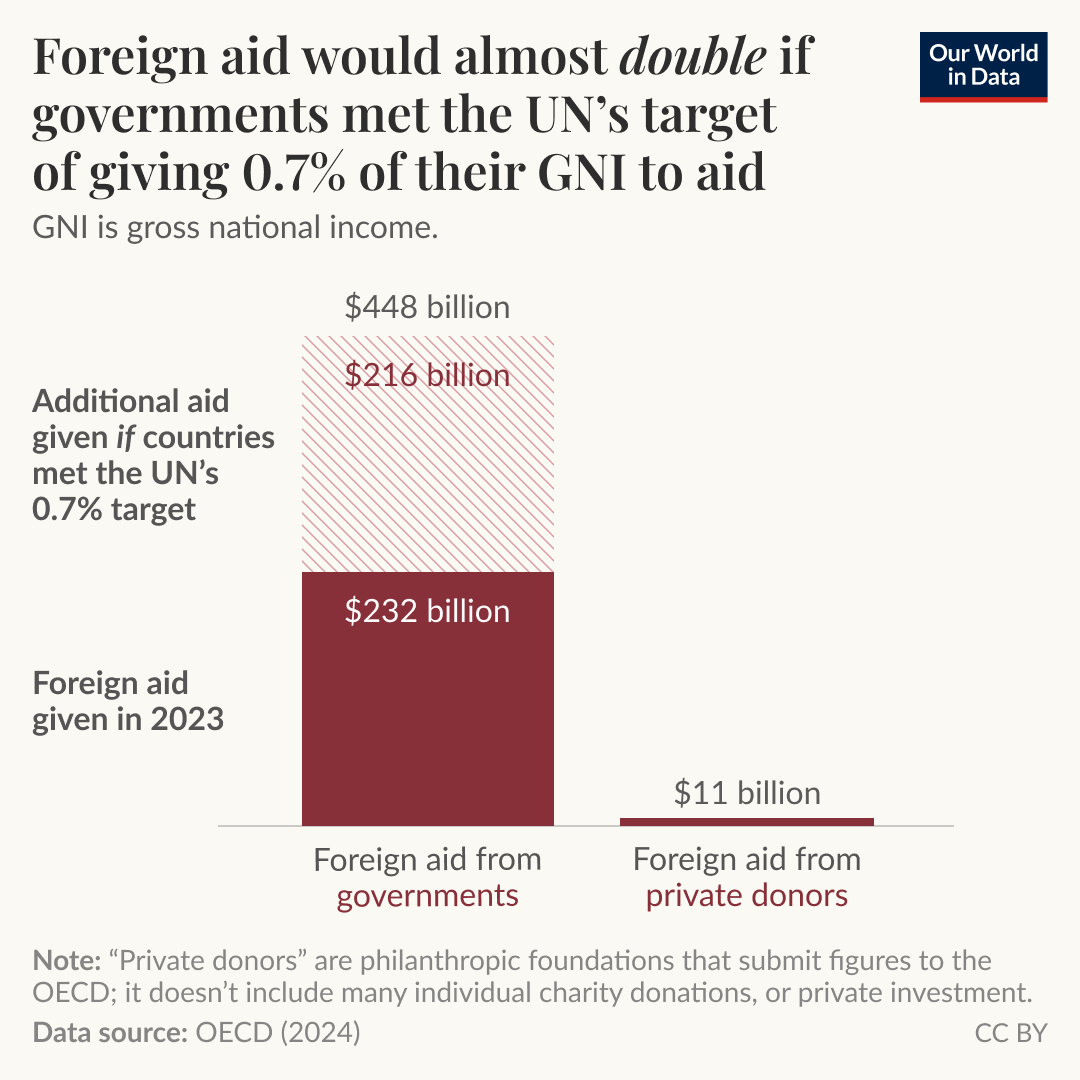

‘These big successes have been achieved with a relatively small amount of money. In 2023, the world gave around $240 billion in foreign aid — a tiny fraction of most rich countries’ economies. In fact, only five developed countries met the UN’s target to give 0.7% of their gross national income (GNI) to foreign aid.

‘As you can see in the chart, most aid comes from governments, not large private philanthropic donors. This means that citizens can strongly influence the global aid budget by building public support for more generous aid budgets from our governments.

‘Let’s imagine that the public in developed countries pressured their governments to step up and meet the UN’s 0.7% target. If all developed countries achieved this, we’d add an extra $216 billion, almost doubling the amount of foreign aid from governments.

‘In a new article, Hannah Ritchie gives an overview of current foreign aid spending, and shows how even small differences could make a big difference.’

ourworldindata.org | @OurWorldInData | @_HannahRitchie

Hantavirus Hackman—David Waltner-Toews

For those interested in knowing more about the zoonotic disease known as Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, which caused the death of 65-year-old Betsy Arakawa, wife of Gene Hackman, Canadian epidemiologist and writer David Waltner-Toews posted a note on his LinkedIn page linking to an article he posted on his website from his 2020 book On Pandemics:

Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome, from the Chapter on Splashing through Rat Piss, in On Pandemics: Deadly Diseases from Bubonic Plague to Coronavirus by David Waltner-Toews, Greystone Press, May, 2020

‘While we are on the subject of problems associated with rodents, it is worth mentioning hantaviruses. This family of viruses is spread from small, wild rodents to people when the animals’ saliva, feces, and urine are aerosolized, and people breathe it in with dust. Not a pretty thought.

‘The Four Corners area of the southwestern United States is a Navajo Tribal Lands area on a high plateau where Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona meet. In the spring of 1993, people began wandering into local medical centers with what at first appeared to be common flu-like symptoms: fever, muscle aches, coughing. The only trouble was that after the first day or so, the illness it didn’t behave like the flu. Of the first dozen or so who showed up at the medical centers, about three-quarters died rapidly from respiratory failure. In the week after May 14, near Gallup, New Mexico, a young athlete, his fiancée, and four other people died. Over that summer, dozens more people came down with this new disease, and the case-fatality rate dropped, but not dramatically enough to make everyone relax.

‘The CDC did what it does best. It mounted a concerted effort to isolate and identify the infectious agent, right down to its molecular structure. . . . They were able to identify a previously unidentified hantavirus, which was named, appropriately, sin nombre (“no-name”). The disease was called hantavirus pulmonary syndrome.

‘Since 1993, scientists have learned a lot about this family of viruses. . . . The actual virus wasn’t identified until 1976, when Korean investigator Ho-Wang Lee isolated it and named it Hantaan virus, after a river in the demilitarized zone, where the disease is common. . . .

‘Since [the time of the 1993 outbreak], an increasing number of cases and outbreaks have been recognized in North and South America, and a great variety of both viruses and rodent reservoirs have been identified. Researchers have also done detailed investigations into the lives of small rodents, their diseases, and human relationships to them. Apart from the Norway rat, which can carry the disease, other carriers include the deer mouse, white-footed mouse, bandicoot rat, meadow vole, reed vole, musk shrew, European common vole, yellow-neck mouse, small-eared pygmy rice rat, Mexican harvest mouse, cotton rat, prairie vole, California vole, vesper mouse, long-tailed pygmy rice rat, and Siberian lemming. . . .

Many cases in North America occur when people clean out cottages in the spring, disturbing nests and sending up clouds of mouse excretions.

‘Between 1989 and 2015, 109 cases and 27 deaths were reported in Canada. In the US, 728 cases and 262 deaths were reported between 1993 and 2017. Although disturbing the nests of rodents explains many individual cases, it doesn’t usually explain outbreaks. In these instances, some combination of human behavior and ecological change is usually at work. . . .

The message of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome for North Americans is that we should wear face masks while cleaning out the cottage and be especially careful after a mild, rainy winter and spring.

Yet there is another, larger message that the rodents have for us, expressed in a language that has yet to be translated into those of politicians and land developer. . . . If wealthy people can sometimes protect themselves from ills carried by rodents, I confess it gives me some small satisfaction to see how the subtle voices of nature manage to slip past our expensive and sophisticated technico-medical defenses and catch our notice. Rodent excreta in the cottage. Rodent piss in the lake. “We are in the air,” their message whispers. “We are in the water. Welcome to our world.”’

davidwaltnertoews.wordpress.com

History isn’t entirely repeating itself in Covid’s aftermath—Gina Kolata

Five years after the novel coronavirus emerged, historians see echoes of other great illnesses, and legacies that are unlike any of them.

‘Five years after Covid-19 shut down activities all over the world, medical historians sometimes struggle to place the pandemic in context.

‘What, they are asking, should this ongoing viral threat be compared with?

‘Is Covid like the 1918 flu, terrifying when it was raging but soon relegated to the status of a long-ago nightmare?

‘Is it like polio, vanquished but leaving in its wake an injured but mostly unseen group of people who suffer long-term health consequences?

‘Or is it unique in the way it has spawned a widespread rejection of public health advice and science itself, attitudes that some fear may come to haunt the nation when the next major illness arises?

‘Some historians say it is all of the above, which makes Covid stand out in the annals of pandemics.

‘In many ways, historians say, the Covid pandemic—which the World Health Organization declared on March 11, 2020—reminds them of the 1918 flu. Both were terrifying, killing substantial percentages of the population, unlike, say, polio or Ebola or H.I.V., terrible as those illnesses were.

‘The 1918 flu killed 675,000 people out of a U.S. population of 103 million, or 65 out of every 10,000. Covid has so far killed about 1,135,000 Americans out of a population of 331.5 million, or 34 out of every 10,000.

‘Both pandemics dominated the news every day while they raged. And both were relegated to the back of most people's minds as the numbers of infections and deaths fell.

‘J. Alexander Navarro, a medical historian at the University of Michigan, said that in the fall of 1918, when the nation was in the throes of the deadliest wave of the 1918 flu, “newspapers were chock-full of stories about influenza, detailing daily case tallies, death tolls, edicts and recommendations issued by officials.”

‘During the next year, the virus receded. And so did the nation’s attention.

‘There were no memorials for flu victims, no annual days of remembrance.

‘“The nation simply moved on,” Dr. Navarro said.

‘Much the same thing happened with Covid, historians say, although it took longer for the virus’s harshest effects to recede.

‘Most people live as though the threat is gone, with deaths a tiny fraction of what they once were.

‘In the week of Feb. 15, 273 Americans died of Covid. In the last week of 2021, 10,476 Americans died from Covid.

‘Interest in the Covid vaccine has plummeted, too. Now just “a measly 23 percent of adults” have gotten the updated vaccine, Dr. Navarro noted.

‘Remnants of Covid remain—lasting financial effects, lags in educational achievement, casual dress, Zoom meetings, a desire to work from home. But few think of Covid as they go about their daily lives.

‘Dora Vargha, a medical historian at the University of Exeter, noted that there had been no ongoing widespread effort to memorialize Covid deaths. Instead, with Covid, “people disappeared into hospitals and never came out.”

‘Now it is only their friends and families who remember.

‘Dr. Vargha called that response understandable. People, she said, do not want to be “dragged back” into memories of those Covid years.

‘But some, like those suffering from long Covid, can’t forget. In that sense, she sees parallels with other pandemics that, unlike the 1918 flu, left a swath of people who were permanently affected.

‘People who contracted paralytic polio in the 1950s described themselves to Dr. Vargha as “the dinosaurs,” reminders of the time before the vaccine, when the virus was killing or paralyzing children.

‘Every pandemic has its dinosaurs, she said. They are the Zika babies living with microcephaly. They are the people, often at the margins of society, who develop AIDS.They are the people who contract tuberculosis.

‘But despite the pleas from those who cannot forget Covid and who seek more research, more empathy, more attention, the more pervasive attitude is, “We don’t need to care anymore,” said Mary Fissell, a historian at Johns Hopkins University. . . .

‘One aspect of the Covid pandemic, though, is still with the nation, and seems to be part of a new reality: It has markedly changed attitudes toward public health.

‘Few medical experts . . . expected so much resistance to measures like masks, quarantines, social distancing and—when they became available—vaccines and vaccine mandates.

‘With Covid . . . compared to other pandemics, the amount of pushback to standard public health practices was remarkable.’

‘That sets Covid apart . . . . Public health measures that had worked in the past were rejected . . . .

With Covid, ‘faith in the scientific process got lost,’ Dr. Lerner said.

That does not bode well for the next pandemic, Dr. Harper said.

‘There’s going to be another pandemic,’ he said. ‘And if we have to fight it without public trust, that’s the worst possible response.’

nytimes.com | @nytimes | @ginakolata

15 lessons scientists learned about us when the world stood still—Claire Cain Miller and Irineo Cabreros

The pandemic gave researchers a rare opportunity to study human behavior. Their work offers lessons about loneliness, remote work, high heels and more. . . . For now, here are 15 things we learned.

1. Flu season doesn’t have to be so bad. . . .

2. Home-field advantage got less mysterious. . . .

3. Teenagers need to sleep in, but schools won’t let them. . . .

4. High heels aren’t just uncomfortable—they’re dangerous. . . .

5. Patients don’t always need to see a doctor in person, if at all. . . .

6. Women are better patients than men. . . .

7. Not even being stuck at home makes men do more housework. . . .

8. Alcohol restrictions can save lives. . . .

9. Office workers don’t need to be chained to their desks. . . .

10. Computers are no replacement for classrooms. . . .

11. There’s a simple way to bring children out of poverty. . . .

12. Premature births might be prevented by taking care of moms. . . .

13. Dolphins talk more when people aren’t around. . . .

14. Trees and plants make people happier. . . .

15. There’s no substitute for human contact. . . .

nytimes.com | @nytimes | @clairecm | @cabrerosic

Four ways COVID changed virology: Lessons from the most sequenced virus of all time—Ewen Callaway

After 150,000 articles and 17 million genome sequences, what has science taught us about SARS-CoV-2?

‘. . . In just five years, SARS-CoV-2 became one of the most closely examined viruses on the planet. Researchers have published about 150,000 research articles about it, according to the citation database Scopus. That’s roughly three times the number of papers published on HIV in the same period. Scientists have also generated more than 17 million SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences so far, more than for any other organism. This has given an unparalleled view into the ways in which the virus changed as infections spread. “There was an opportunity to see a pandemic in real time in much higher resolution than has ever been achievable before,” says Tom Peacock, a virologist at the Pirbright Institute, near Woking, UK.

‘Now, with the emergency phase of the pandemic in the rear-view mirror, virologists are taking stock of what can be learnt about a virus in such a short amount of time, including its evolution and its interactions with human hosts. Here are four lessons from the pandemic that some say could empower the global response to future pandemics—but only if scientific and public-health institutions are in place to use them.

‘On 11 January 2020, Edward Holmes, a virologist at the University of Sydney, Australia, shared what most scientists consider to be the first SARS-CoV-2 genome sequence to a virology discussion board; he had received the data from virologist Zhang Yongzhen in China.

‘By the year’s end, scientists had submitted more than 300,000 sequences to a repository known as the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID). The rate of data collection only got faster from there as troubling variants of the virus took hold. Some countries ploughed enormous resources into sequencing SARS-CoV-2: between them, the United Kingdom and the United States contributed more than 8.5 million (see ‘Viral genome rally’). Meanwhile, scientists in other countries, including South Africa, India and Brazil, showed that efficient surveillance can spot worrying variants in lower-resource settings. . . .

During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers shared more than 300,000 genome sequences of the virus SARS-CoV-2 through the global science initiative GISAID. The pace of sequencing quickened drastically, but then levelled off during 2024.

‘In earlier epidemics, such as the 2013–16 West African Ebola outbreak, sequencing data came in too slowly to track how the virus was changing as infections spread. But it quickly became clear that SARS-CoV-2 sequences would arrive at an unprecedented volume and pace . . . .

‘“It became possible to track the evolution of this virus in tremendous detail to see exactly what was changing,” says Jesse Bloom, a viral evolutionary biologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle, Washington. With millions of SARS-CoV-2 genomes in hand, researchers can now go back and study them to understand the constraints on the virus’s evolution. “That’s something we’ve never been able to do before,” says Hodcroft. . . .

Influenza spreads mainly through the acquisition of mutations that allow it to evade people’s immunity. Because no one had ever been infected with SARS-CoV-2 before 2019, many scientists didn’t expect to see much viral change until after there was substantial pressure placed on it by people’s immune systems, either through infections or better yet, vaccination.

The emergence of faster-transmitting, deadlier variants of SARS-CoV-2, such as Alpha and Delta, obliterated some early assumptions. Even by early 2020, SARS-CoV-2 had picked up a single amino-acid change that substantially boosted its spread. Many others would follow.

‘. . . The initial giant leaps that SARS-CoV-2 took came with one saving grace: they didn’t drastically affect the protective immunity delivered by vaccines and previous infections. But that changed with the emergence of the Omicron variant in late 2021, which was laden with changes to its “spike” protein that helped it to dodge antibody responses (the spike protein allows the virus to enter host cells). Scientists such as Bloom have been taken aback at how rapidly these changes appeared in successive post-Omicron variants. . . .

‘And although Omicron and its offshoots were milder than Alpha, Beta and Delta, those had all proved more virulent than the lineage they replaced, toppling the idea that the virus would evolve to be less deadly.

‘The idea that there’s some law of nature that says that a virus is going to rapidly lose its virulence when it jumps into a new host is incorrect,’ Bloom says. It’s an idea that never had much buy-in with virologists anyway.

‘One of [Kei] Sato’s big fears is that a drastically different SARS-CoV-2 variant will emerge and overcome the immunity that stops most people becoming severely ill. He worries that the result could be disastrous. . . .’

nature.com | @nature | @ewencallaway

With Manus, AI experimentation has burst into the open—The Economist

The old ways of ensuring safety are becoming increasingly irrelevant

‘Watching the automatic hand of the Manus AI agent scroll through a dozen browser windows is unsettling. Give it a task that can be accomplished online, such as building up a promotional network of social-media accounts, researching and writing a strategy document, or booking tickets and hotels for a conference, and Manus will write a detailed plan, spin up a version of itself to browse the web, and give it its best shot.

‘Manus AI is a system built on top of existing models that can interact with the internet and perform a sequence of tasks without deferring to a human user for permission. Its makers, who are based in China, claim to have built the world’s first general AI agent that “turns your thoughts into actions”. Yet AI labs around the world have already been experimenting with this “agentic” approach in private. What makes Manus notable is not that it exists, but that it has been fully unleashed by its creators.

A new age of experimentation is here, and it is happening not within labs, but out in the real world.

‘Spend more time using Manus and it becomes clear that it still has a lot further to go to become consistently useful. Confusing answers, frustrating delays and never-ending loops make the experience disappointing. In releasing it, its makers have obviously prized a job done first over a job done well.

‘This is in contrast to the approach of the big American labs. Partly because of concerns about the safety of their innovations, they have kept them under wraps, poking and prodding them until they hit a decent version 1.0. OpenAI waited nine months before fully releasing GPT-2 in 2019. Google’s Lamda chatbot was functioning internally in 2020, but the company sat on it for more than two years before releasing it as Bard.

Big labs have been cautious about agentic AI, too, and for good reason. Granting an agent the freedom to come up with its own ways of solving a problem, rather than relying on prompts from a human at every step, may also increase its potential to do harm.

‘. . . The existence of Manus makes this cautious approach harder to sustain, however. As the previously wide gap between big AI labs and upstarts narrows, the giants no longer have the luxury of taking their time. And that also means their approach to safety is no longer workable. . . .

‘Instead, regulators and companies will need to monitor what is already used in the wild, rapidly respond to any harms they spot and, if necessary, pull misbehaving systems out of action entirely. Whether you like it or not, Manus shows that the future of ai development will play out in the open.’

economist.com | @TheEconomist

Arresting headlines

Second death reported as measles cases climb in Texas, New Mexico: The measles outbreak in Texas rises to 198 cases, while New Mexico's outbreak climbs to 30 cases—CIDRAP

Why health experts fear the West Texas measles outbreak may be much larger than reported: For some, it’s a question of simple math—STAT News

New AI agent unveiled in the latest win for China in the global tech race: A new artificial intelligence agent developed by Chinese researchers is reinforcing fears Beijing is eclipsing the US in the AI race. Manus AI claims to be the world’s first fully autonomous AI agent, meaning it can carry out complex tasks without oversight. Forbes described it as ‘a digital polymath.’—Semafor

Ancient ancestor of the plague discovered in Bronze Age sheep: The DNA of Yersinia pestis bacteria has been found in a Bronze Age sheep, offering a clue to how the plague may have spread through prehistoric farming communities—New Scientist

Bird flu-infected San Bernardino County dairy cows may have concerning new mutation: A genetic mutation has appeared in dairy cows that could make the virus more deadly and transmissible—Los Angeles Times

Deadly avian flu strain is spreading rapidly in Antarctica: Expedition finds H5N1 in 13 bird and seal species on the Antarctic Peninsula—Science (h/t Helga Recke)

H5N1 bird flu virus is infectious in raw milk cheese for months, posing risk to public health, study shows: Raw cheese made with milk from dairy cattle infected with bird flu can harbor infectious virus for months and may be a risk to public health, according to a new study from researchers at Cornell University that was funded by the US Food and Drug Administration. Raw milk cheeses are those made with milk that hasn’t been heat-treated, or pasteurized, to kill germs—CNN (h/t Lynn Brown)

The Japanese town turning cowpats into hydrogen fuel: In Japan, a smelly waste product is being reimagined as a potential clean fuel of the future that is powering cars and tractors—BBC (h/t Helga Recke)

Have you by any way come across information pertaining to the Covid19 and how it occurred in 13% of the more than 2000+ blood samples taken in Italy in the period April to September 2019, meaning 8 to 3 months prior to the outbreak allegedly initially occurring in Wuhan in December 2019?

Have you by any chance come across information in regards to the original ACE2 attack vector of the Covid19, which is said to contain a highly specialized genetic sequence - where that particular sequence does not exist in any of the known 1500 species of Corona virus - and where that particular - pretty short - sequence does also occur as part of a Moderna Patent on a genome dating back to 2016?

Have you had any contact or information about the particular genetic sequence CGG-CGG, which is - as I get it - a less common sequence in the genome of living beings, but, which occur more frequently in the above mentioned ACE2 attack vector, than in usual living beings, and where this sequence is disfavoured during normal reproductive genetic exchanges, while it occurs more often in genetic splicings performed via CRISPR?

I am asking these questions as you appear quite knowledgeable in the matter of SARS-COV2, and as I have only heard about these things and have remembered them so that I can ask someone who really may know the truth, one day - perhaps you - ???

I hope that you are doing well. I have moved back to Denmark as I was unable to get work permit without having to bribe myself through, which I refused.

Sincerely

David Svarrer